Politicon.co

Indian education system

History in Perspective: Education System As a Colonial Tool

The 19th century British colonization of India is often regarded as a milestone in Indian culture. The Colonists are frequently credited by modern day historians for establishing relative peace, constructing critical infrastructure, leading industrialization, banning obsolete practices such as sati [2] and child marriage, and spreading Western ideas. From this standpoint, past British imperialism can be consideredas overall beneficial to India, evoking some sympathy towards the concept of colonialism as well. While some benefits of 200 year British rule cannot be dismissed, one pertinent question remains — does beneficial always mean benevolent?

To examine this question, our team decided to investigate one specific aspect of British colonialism — education — and how it was abused as a political tool.

Benevolence or just business?

After the invasion of parts of India by the British East India Company, a grave need for social order emerged in the colony—an order which had to be enforced with minimal amount of violence so as to not disrupt colonial commerce [2]. One of the most viable ways to impose such order was to brush the concept of “[colonial] citizen morality” into the public mindset through peaceful agents such as education. Indeed, principles of order and morality were echoed in all chambers of government administration, and education constituted no exception; order was the body of education and morality its soul.

British colonial education revolved heavily around the concept of “Macaulayism,” or the use of educational propaganda to legitimize the actions of colonists while simultaneously developing the Indians’ disdain for their own culture[3] . The British belief at that time was that the Asiatic societies were on the brink of moral depravity and complete ignorance and that it was the enlightened West’s humanistic duty to “civilize” those masses[5]. By labeling colonial expansion the white man’s (and later white woman’s) “burden,” the colonial government could avoid being held accountable both internationally and locally.

The most obvious reason behind the establishment of educational system in India, to our analysis, was its role as a clerk producing machine. The Englishmen willing to work for the East India Company demanded reasonable wages while India was brimming with much cheaper and more accessible labor. As John Malcolm, the Governor of Bombay between 1827 and 1830, stated, “the expenses of the company could be reduced by allowing some of the services to be performed by “natives on diminished salaries.”[5] Official statements of Francis Warden, the director of East India Company during 1836-1850, testify the commercial interests of the British education system: “education, as a Government concern, would be expensive without being beneficial,” and the best way to make it “beneficial” is “judicious encouragement” of the higher sections of Indian society. To sum up with the analysis of Krishan Kumar, British historian and sociologist, “state spending on the education could be explained mainly as investment in preparation of trustworthy, cheap subordinates.” It is not surprising that two years after Indians were allowed to enter company’s service under the Saint Helena Act of 1833, the language of the curriculum was changed to English through English Education Act.

The Nature of Education

The emphasis on morality was mainly reflected by the dominance of arts and humanities, thought to shape people’s mentality, in the colonial curriculum. The prevailing belief of the time was that books which did not teach one “good morals” carried little value. But the question is, was the concept of “good morals” a universal term in 19th century, and if it was not, who defined this concept? The answer to this question can be found nowhere more clearly expressed than in the minute recorded by Thomas Babington Macaulay. Macaulay was the first Law Member of the Governor-General's Council who argued for complete replacement of Orientalist education system with an Anglicist one, and it was during his service that the language of the Indian curriculum was changed to English. In his minute published on 2 February, 1835 as a response to debates relating to education, Macaulay argued that the “intrinsic superiority of Western literature” cannot be denied and that “...a single shelf of a good European library is worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.” The debates about the design of Indian curriculum resulted in the English Education Act of 1835. Through this act, the Anglicist education system was ultimately adopted, eradicating entirely Oriental elements in curriculum. From this point on, the colonial nature of the Macaulayist education started to tip the surface. Literature classes covered mainly English writers, especially Shakespeare, Addison, and Bacon, while classical line of Persian works like Gulistan and Bustan of Saadi were abandoned; History focused on the benefits of Western colonialism and demonstrated the inherent superiority and enlightenment of British race; Economics was taught as a mechanism of materialism and capitalism[6]. On the other hand, science education, which did not incorporate elements of morality and obedience, remained largely underfunded. Indeed, until 1899, the only institution that offered a separate degree in sciences was the University of Bombay[7].

Deliberate Perpetuation of Inequalities

The stark differences between upper and lower class education present for centuries did not stop haunting Indian culture at the colonial stage of her development as well. The education of lower classes unilaterally stressed morality, obedience, and “good” behavior. The curricula prepared for the lower castes put its main focus on religious or quasi-religious literature (Christian, mainly) that instilled modesty and acceptance of one’s social status in the Earthly life. The upper class students, however, had the opportunity to focus on classical languages, literature, sciences, and skills pertaining to reflection and inquiry. Such wild educational opportunities afforded to higher social classes could be explained, from one perspective, by the liberal perception of the time that the state’s main duty was to maintain suitable conditions for enhancement of “pleasure of the man who could enjoy himself.” The state, therefore, tried to fulfill this duty by giving a dual arrangement to the applied education system. On the other hand, the British perspective on education stressed the idea that the best way to advance the moral and intellectual welfare of a nation while also manipulating it was — instruction of higher social strata. By psychologically indoctrinating the elite layer, the government tried to form model British subjects[8]. The government successfully differentiated those “models” by granting them certifications, medals, and mark sheets, by enabling them to read and write in English, and most importantly, by making them eligible for state employment [9]. As J.N.Farquhar, a contemporary commenter on the colonial education system quoted, “these are men who think and speak in English habitually, who are proud of their citizenship in the British Empire, who are devoted to English literature, and whose intellectual life has been almost entirely formed by the thought of the West, large numbers of them enter government services, while the rest practice law, medicine or teaching, or take to journalism or business” [10]. In more explicit words of Macaulay, the very people who ruled India had to be “Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.” [11]

To further perpetuate this lack of equality, the colonists turned to legalization of the caste system—that is, a religious order which divides Hindus irrevocably into different classes based on birth. Although the caste system was used before British colonization (and harshly condemned by many British representatives), it became legally codified during their conquest. This is, one more time, a manifestation of bourgeois interests advanced under the curtain of education [12].

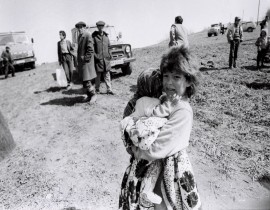

Apart from widening the gap between those who participate in education, the colonist involvement made it even harder for ordinary civilians to participate in educational activity. While in 1851, there was one school for every 1,783 civilians in one district in Punjab, by 1881, one school stood for every 9,028 civilians[13]. Additionally, in North India, Parliament established classes in Urdu as opposed to the local languages[14], thus, unintentionally excluding many members of society from education, including Hindu priests, artisans, and farmers.[15] This negligence blatantly reveals how Indian civilians had far less accessibility to education after implementation of British education system.[16]

Regarding the gender inequality in education, the situation did not seem to improve even after the cultural descent of the “enlightened” West. Male education was still being typically valued over female one. Reformers within India previously taught women to “emphasize moral and spiritual values” without becoming too exposed to “Western ideas.” This idea was continued by the colonists after colonization when they held women responsible for “maintaining the new morality” that the British had established.[17]

Conclusion

Despite these conclusions, there are still some claims that Britain’s and its predecessor’s colonizing work during this time was an act of benevolence and was fundamental to the overall growth of India. While the colonization process, including education, was of certain value for development of India, the intentions behind it were far from being purely developmental. Many British colonists did not see any value in Indian culture nor were they interested in seeing one. Not unlike most colonists, their main concern was to exploit their colonies to their capitalist advantage, and this process sometimes, as our research attempted to demonstrate, took very subtle forms like education. The legacy of such colonial exploitation still haunts India. Today, the elite Indian class governs in English and high-level universities are predominantly run based on English customs. However, just 30 percent of Indians today are able to fluently speak English, preventing the rest 70% majority from being able to move higher up in the social ladder.[18] Low social mobility caused by Anglo-centric education, in its turn, further aggravates the socioeconomic inequalities persisting in India. Through education, as India’s today proves, British colonizers replaced one caste system with another.

[1] A former funeral practice in India whereby a widow threw herself onto her husband's pyre. Sati was banned in 1829 by the British East India Company under the supervision of Lord William Bentinct, then Governor-General, through the Bengal Sati Regulation. For more information see Wikipedia.

[2]Kumar, Krishan. Political Agenda of Education: A Study of colonialist and Nationalist Ideas. 2nd ed. New Dehli: SAGE publications, 2005.

[3] Masani, Zareer. "How Thomas Macaulay 'educated' India." Firstpost. 13 Nov. 2012. Web. 06 Aug. 2017.

[4] Kumar, Krishan . Political Agenda of Education: A Study of colonialist and Nationalist Ideas.2nd ed. New Dehli: SAGE publications, 2005.

[5] Kumar, Krishan . Political Agenda of Education: A Study of colonialist and Nationalist Ideas.2nd ed. New Dehli: SAGE publications, 2005.

[6] Kumar, Krishan . Political Agenda of Education: A Study of colonialist and Nationalist Ideas 2nd Editon. 2nd ed. New Dehli: SAGE publications, 2005.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Malik, Muhammad Akbar, Aftab Hussain Gillani, and Muhammad Imran Jaffar. "Critical Review of British Education System in India." Journal of Educational Research 13, no. 2.

[9] Kumar, Krishan . Political Agenda of Education: A Study of colonialist and Nationalist Ideas 2nd Editon. 2nd ed. New Dehli: SAGE publications, 2005.

[10] Malik, Muhammad Akbar, Aftab Hussain Gillani, and Muhammad Imran Jaffar. "Critical Review of British Education System in India." Journal of Educational Research 13, no. 2.

[11] Zastoupil, Lynn, and Martin I. Moir. The great Indian education debate: documents relating to the Orientalist-Anglicist controversy, 1781-1843. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016.

[12] Kumar, Krishan . Political Agenda of Education: A Study of colonialist and Nationalist Ideas 2nd Editon. 2nd ed. New Dehli: SAGE publications, 2005

[13] The National Review. Vol. 2. London: W.H. Allen & Co, 1883-84.

[14] Swarup, Ram. On Hinduism: Reviews and Reflections. New Delhi: Voice of India, 2000. Print.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Abel, James F. "History of Education in the Far East." Review of Educational Research 9, no. 4 (1939): 381-90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1167569.

[17] French, Marilyn. From Eve to dawn: a history of women. Vol. 4. New York: The Feminist Press, 2008. Print.

[18] Flows, Capital. "The Problem With The English Language In India." Forbes. November 06, 2014. Accessed August 07, 2017.

![]()

- TOPICS :

- Society

- REGIONS :

- South Asia

jpg-1599133320.jpg)