Politicon.co

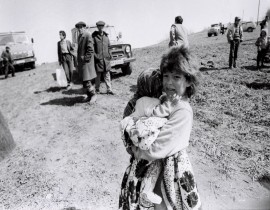

Media, identity, and belonging in Karabakh: communication strategies for social reintegration

Introduction

Karabakh is not only a historical conflict zone, but also a multi-layered socio-political area where identity, belonging and social memory collide. The reintegration policies implemented by the Azerbaijani state after the Second Karabakh War, which ended in 2020, include not only physical return but also the reconstruction of the social fabric. The function of media narratives in identity construction is analyzed with the theoretical framework created through Benedict Anderson's "imagined community" approach, Henri Tajfel's social identity theory and Manuel Castells' "network society" conceptualizations. In addition, a comparative assessment is made on similar post-conflict examples from the South Caucasus, Georgia and the Balkans, and original communication strategies are suggested for Karabakh.

Today, the sense of “belonging” in Karabakh, both for returning migrants and the settled population, often creates a tension between nostalgia and reality. This tension is not only observed in individual psychologies but also in public discourses and media representations. Therefore, the question of whether a bridge can be established between this duality through the media is at the center of the study. In addition, the reconstruction strategy pursued by media institutions against technical, social and political challenges in the region is another dimension of the research. In this context, the article analyzes the current media reality in Karabakh; then discusses communication strategies that will strengthen social integration on a normative, applied and critical level. As a result, the aim of the study is to develop a sustainable and inclusive communication model that will facilitate the reconstruction of identity and belonging through the media.

Theoretical Framework

Henri Tajfel's theory of social identity suggests that individuals formalize their identities by belonging to certain social groups. Essentially, with this theory, people create the distinction between “us” and “them” by prioritizing their own groups over others. The idealist identity, which was established on the "displaced lands" that were formed during the period of forced displacement, is today surrounded by reality. In the era of new social reintegration, it is important to redefine this identity.

The new generation living in Karabakh encounters more complex and mixed identities, unlike the previous generation. Here the concept of "hybrid identity" becomes actual. Hybrid identity involves the individual's identity being formed among several civil and social systems. This approach is especially useful in showing how the people who lived in the past changed under the influence of the city, the city, and the various social layers (Ormeci, O., 2023).

Benedict Anderson’s concept of “imagined society” argues that the concept of nation is not a physical, but an imaginary and media-based unity. According to this theory, people, even if they do not know each other personally, form a common sense of “we” through the media. In the case of Karabakh, this sense of “we” has been shaped by the state and national media over the years through patriotism.

Manuel Castells’s “network society” approach explains how digital communication and social media are changing the identity and social participation of individuals. As information and infrastructure are restored in Karabakh, the role of social networks is increasing. According to Castells, people now define their social positions not locally, but through global networks. This leads to the emergence of more mobile, flexible and multifaceted identity models for the new generation of Karabakh residents. The function of the media here is not simply to provide information, but to create belonging within social networks.

When Anderson and Castells’ approaches are analyzed together, both “national imagination” and “digital participation” play an important role in the reintegration process in Karabakh. The language of the media, the images and stories it chooses, shape these imagined identities.

Media and Identity in the Post-Conflict Context

In Georgia, the establishment of independent control mechanisms over state media after the 2008 Ossetia War; ensuring compliance with broadcasting principles through the National Broadcasting Board (GNBC) paved the way for increased content diversity. In the Balkans, the establishment of joint broadcasting protocols that pay attention to ethnic balance by Serbian, Bosnian and Albanian media organizations in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo have been concrete steps towards inclusive journalism. In the Balkan countries, local NGOs and independent producers have established local radio stations financed by international funds and broadcasted both education and reconciliation programs; “Media Literacy Workshops” have provided democratic participation skills to both young people and returnees. In Georgia, the “Journalism for Peace” initiative has provided mentoring support for small-budget documentary and news projects, thus ensuring the rise of civil voices in rural areas. Fund pools based on international NGO collaborations should be established for similar mechanisms in Karabakh, and capacity-building programs for local journalists should be implemented urgently.

In the Balkans, satellite radio has been expanded in the post-conflict period, and portable 4G base stations have been put into service in rural areas where internet access is weak. In Georgia, digital verification platforms such as Check.ge have served as models in the fight against disinformation. In Karabakh, in addition to Facebook and Telegram, the development of local verification applications that serve the same function and the creation of active moderator pools by civil society will increase the reliability of information.

Emphasis on pluralism: In both Georgia and the Balkans, joint production formats that transcend ethnic boundaries can serve as examples of “common history” projects in Karabakh.

Independent regulatory bodies: Autonomous editorial boards at national and regional levels should be taken as models for monitoring content standards. Sustainable partnerships should be developed between local media producers and NGOs through the use of international funds. The mobile base stations implemented in the Balkans and the fact-checking platforms in Georgia can be adapted to alleviate Karabakh’s technical infrastructure problems.

This comparative analysis demonstrates that post-conflict media reconstruction in Karabakh; It can be strengthened with lessons to be learned from the examples of Georgia and the Balkans in terms of institutional reform, content pluralism, civil society participation and technology transfer. Thus, it will be possible for the region to achieve its goal of social reintegration with a more inclusive and effective media strategy (Aliyeva, G., 2021).

Regional review

In post-traumatic societies, media can be part of both memory and healing processes. Psychologically, listening to others’ stories through media fosters empathy. For people living in Karabakh under the influence of conflict for years, the role of media is not just to provide information, but also to build emotional bridges. Narrative-oriented reports and documentaries can serve this purpose. This can create the effect of “understanding the pain of another.”

Empathy is one of the main conditions for social reintegration. By bringing together different experiences, media can create emotional understanding between different layers of society. Without this understanding, social integration cannot be successful. Cognitive restructuring is essential for changing people’s stereotypes and attitudes about the conflict. Media can provide a platform for this restructuring. For example, informative and positive content about the current development of a region that was previously portrayed as an enemy should be presented (Khalilov, R., 2020).

Communication Strategies for Social Reintegration

Media activities in the Karabakh region face challenges such as inadequate infrastructure and limited local initiatives to support social reintegration. Physically damaged broadcast transmitters and communication lines have significantly reduced the capacity of radio and television broadcasting in the region. Mobile operator coverage gaps, inadequate internet speeds, and power outages threaten the continuity of information flow, making it difficult for even official media to reach the region regularly. Therefore, the rapid repair of the communication infrastructure and the commissioning of temporary satellite or portable communication stations should be the first step of the strategy. For example, television and radio channels can present the audience with documentary series that tell the stories of the settlement processes of returning families and the reconstruction of villages and towns. These contents, prepared in cooperation with local governments and civil society organizations, will both strengthen social solidarity and make ongoing rehabilitation efforts transparent. Facebook, Telegram and WhatsApp groups have become the most accessible information channels for the local people. However, the uncontrolled flow of content can cause the spread of false claims such as “news of evacuations in the immediate vicinity” and cause anxiety in the public. Therefore, verification mechanisms, regional media literacy workshops and independent fact-checking teams should be established immediately in the digital environment. Universities and civil society organizations in the media sector can increase local digital resilience by training volunteer moderators.

Content verification mechanisms, local media literacy workshops, and fact-checking units should be urgently established to support reliable news flow on these platforms. Universities and media NGOs can increase regional digital resilience by training volunteer moderators.

The main guiding factors of media activity are the region's communication infrastructure, professional training of journalists, and direct cooperation with local communities. Providing high-speed internet and broadcasting equipment in Karabakh will increase the quality of media products. At the same time, security and field training for journalists should be organized, strengthening their skills in working in difficult conditions. Developing content that takes into account cultural and linguistic characteristics, in cooperation with local experts, will strengthen public trust. The speed and scope of news delivery are expanded through the use of multimedia platforms (podcasts, videos, and interactive maps). Also, regular "open door" meetings should be held between media organizations and civil society, and citizens' suggestions and complaints should be delivered directly to the editorial offices. These measures will ensure both operational and sustainable operation of mediation, and make the region's information network vibrant and reliable (Aliyeva, G., 2021).

All these realities show that the potential of the media in Karabakh is multifaceted, but for this potential to be realized, political will, economic resources and public support must act in parallel (Mehdiyev, R., 2021).

To successfully implement social reintegration in Karabakh, communication strategies should be based on the joint activities of the state, the media, and civil society. First of all, narrative change is of strategic importance. “It is important to move away from the emphasis on opposition in the language of post-war communication and shift to a discourse of unity and cooperation.

For example, state television should broadcast documentaries about the lives of families returning to Karabakh, as well as reports about their problems and hopes. This would serve to build both empathy and mutual understanding (Kaldor, M., 2017).

Bringing the stories of displaced people to the center would create a basis for their voices to be heard and their social visibility. This would facilitate their social integration and strengthen public support.

A multimedia approach — through videos, photos, podcasts, and interactive maps — can help to visually and emotionally construct identity. This approach can be particularly effective for young and technologically-savvy audiences (Dragovic-Soso, J., 2012).

At the same time, communication strategies should also take into account gender, age, social status, and language diversity. For example, radio can be prioritized for older people, and social media content for young people.

Finally, the communication process should be monitored and updated according to the response of the population. In this way, the reintegration strategy can become not only informative, but also a transformative force.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The social reintegration process in Karabakh is closely related not only to infrastructure and security, but also to identity, belonging and communication. In this regard, the media should act not only as a means of information, but also as a social bridge.

In order to address issues of identity and belonging, it is important for the media to move to a model based on empathy and participation. It is essential that human stories are at the center of discussions and that the voices of reintegrated individuals are heard.

Shifting the media language away from the emphasis on conflict and towards peace and development should be encouraged. This is important not only for the domestic audience, but also in terms of international image.

State policies should support public and local media in this direction and encourage new creative initiatives. The rapid development of digital media creates opportunities for these strategies to be delivered to a wide audience.

International experiences show that the more participatory the role of the media in reintegration processes, the stronger social stability and public support. Azerbaijan should benefit from these experiences and direct its media policy in a more open and citizen-oriented direction.

As a result, the success of communication strategies in Karabakh will be measured not only by technical, but also by ethical and social values. These strategies should be considered as one of the main pillars of the psychological adaptation of the population and public solidarity.

References:

-

Aliyeva, Gunel. "Communication and Belonging in Post-War Karabakh: The Role of Local Media Initiatives." Conflict & Communication Online 20, no. 1 (2021): 88–102.

-

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso Books, 2006.

-

Castells, Manuel. The Power of Identity: The Information Age – Economy, Society, and Culture. Vol. 2. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

-

Dragovic-Soso, Jasna. "History of Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Media Narratives." Media, War & Conflict 5, no. 2 (2012): 119–137.

-

Khalilov, Rovshan. "Displaced but Not Disconnected: The Role of Digital Media in Maintaining Community among Azerbaijani IDPs." Journal of Refugee Studies 33, no. 4 (2020): 754–770.

-

Kaldor, Mary. New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era. 2nd ed. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017.

-

Mehdiyev, Ramiz. Media və informasiya təhlükəsizliyi: Müasir çağırışlar və strateji yanaşmalar. Bakı: AMEA Nəşriyyatı, 2021.

-

Örmeci, Ozan. "The Role of Media in Post-Conflict Reconstruction: The Case of Nagorno-Karabakh." Caucasus Strategic Perspective 4, no. 2 (2023): 45–60.

-

Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. "The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior." In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by Stephen Worchel and William G. Austin, 7–24. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1986.

![]()

- TAGS :

png-1748065971.png)

jpg-1599133320.jpg)